(Bloomberg) --American women don’t earn as much as men do, apersistent phenomenon that can’t be explained by disparities ineducation, opportunity or child-bearing. But a growing body ofresearch points to a new and compelling cause: Women make lessbecause of the sexual harassment they face at work.

|The gender-pay gap has hovered under 80 percent fornearly two decades. Most of the discrepancy is because men work inhigher-paying jobs and in more lucrative fields, and most of thepolicy remedies have focused on encouraging women to pursue thosesame, high-paying opportunities.

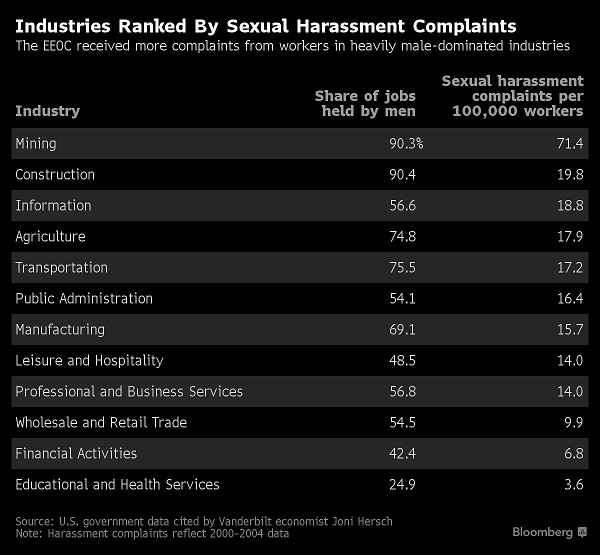

|Months of revelations about sexual harassment and abuse of womenacross industries shed new light on why women don’t “lean in” tohigher-paying jobs more often. Whether they’re earning more becausethey’re in more lucrative fields or because they have more seniorpositions, big paycheck jobs also often pose higher risks of sexualharassment, says Joni Hersch, an economist at VanderbiltUniversity.

|What’s more, women who experience sexual harassment at work aresix-and-a-half times more likely to leave their jobs compared withwomen who don’t, according to research by Amy Blackstone,Christopher Uggen and Heather McLaughlin.

|In one of the only studies that looks at the effects of sexualharassment over time, the sociologists asked about 1,000 men andwomen if they had experienced unwanted touching, offensive jokesand other behaviors that could be considered workplace harassment.Among the female respondents who said they experienced unwantedtouching or at least two of the other, non-physical behaviors, 80percent said they left their jobs within two years.

|When these women leave their jobs, Blackstone said, they don’ttend to trade up. They land in less lucrative fields or positions,a negative economic impact on women that persists through the restof their working years.

|‘It crushed me’

Not long ago, Samantha Ainsley was on the academic fast-track,pursuing a Ph.D. in computer science at MIT, imagining a future ofresearch, consulting and maybe starting her own company.Then shewas assaulted by one of the leading professors in her field at aconference. When she rebuffed him, she says, he continued to try tograb her and accused her of sleeping with fellow students toadvance her career.

|For Ainsley, it was a life-changing event. “All I could thinkabout is, this guy is going to review all of my papers,” she says.“It crushed me.”

|A few months later, she left her program at MIT to work as asoftware engineer at Google, which she described as “a much moremodest career than I had aspired to originally. I had to, in asense, start over.”

||

Lower pay

Understanding exactly how much harassment affects earning powerisn’t easy, said Claudia Goldin, a Harvard professor who studiesthe gender-pay gap. Abuse at work is notoriously under-reported,especially at professional and managerial levels. Someone whoexperienced harassment may ultimately leave her job for anunrelated reason, which wouldn’t show up in traditional economicanalysis.

|At the same time, jobs and fields that are dominated by womenare considered “safer,” according to Hersch’s research. They alsousually pay less.

|Kristian Lum was working as a data scientist in academia whenshe was groped at a professional conference, an incident that, shesays, prompted her to look for work in a new field. She now worksat a nonprofit, in a job that pays less and offers less securitythan if she’d stayed put.

|“I was looking to get away,” she said. “There was a generalfeeling of, ‘I just don’t want to be around this.”’

|Why women leave

There are many factors that influence a woman’s career path, buteven having children -- that notorious career-killer -- may notprompt the same adverse consequences as harassment and its effectson job satisfaction and performance.

|Of female engineers who quit or changed jobs over the five yearsending in 2012, only one-third left to take care of children,according to a 2014 study by Nadya Fouad, a distinguished professorof educational psychology at the University of Wisconsin,Milwaukee. The majority left for better opportunities, broadlydefined, in other fields or companies.

|Similarly, a 2014 study of 25,000 Harvard Business Schoolgraduates found that only 11 percent of female Baby Boomers and GenXers had left the workforce to care for children -- and even amongthose women, the majority left primarily because they saw fewprospects for advancement.

|Hazard premium

Women who persist in hostile environments do earn more. Hersch,the Vanderbilt professor, studies hazard pay -- the premium workersrequire to work in dangerous environments.

|Traditionally, researchers have used on-the-job fatalities orphysical injury to assess whether compensation accounts forphysical risk. Hersch looked at complaints filed with the EqualEmployment Opportunity Commission to determine whether companiesfacing sexual harassment allegations also had to pay workersmore.

|In fact, they do. Women earn on average an extra 25 cents anhour at such companies. Men in jobs known to be hostile earn evenmore: an extra 50 cents an hour, according to Hersch’sresearch.

|For many, a higher paycheck isn’t worth the difficulties ofstaying in a hostile workplace. Women who experience harassment canlose their drive or develop anxiety and depression, any of whichcan have an adverse impact on productivity or performance,according to Lisa Kath, a psychology professor at San Diego StateUniversity who studies workplace harassment. And when those thingsstart to suffer, opportunities for professional advancement -- andhigher earning power -- also decline.

|Copyright 2018 Bloomberg. All rightsreserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten,or redistributed.

Complete your profile to continue reading and get FREE access to BenefitsPRO, part of your ALM digital membership.

Your access to unlimited BenefitsPRO content isn’t changing.

Once you are an ALM digital member, you’ll receive:

- Critical BenefitsPRO information including cutting edge post-reform success strategies, access to educational webcasts and videos, resources from industry leaders, and informative Newsletters.

- Exclusive discounts on ALM, BenefitsPRO magazine and BenefitsPRO.com events

- Access to other award-winning ALM websites including ThinkAdvisor.com and Law.com

Already have an account? Sign In

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.