Even in deep-red states enamored of immigrationcrackdowns, punishing business is bad politics. (Photo:Shutterstock)

Even in deep-red states enamored of immigrationcrackdowns, punishing business is bad politics. (Photo:Shutterstock)

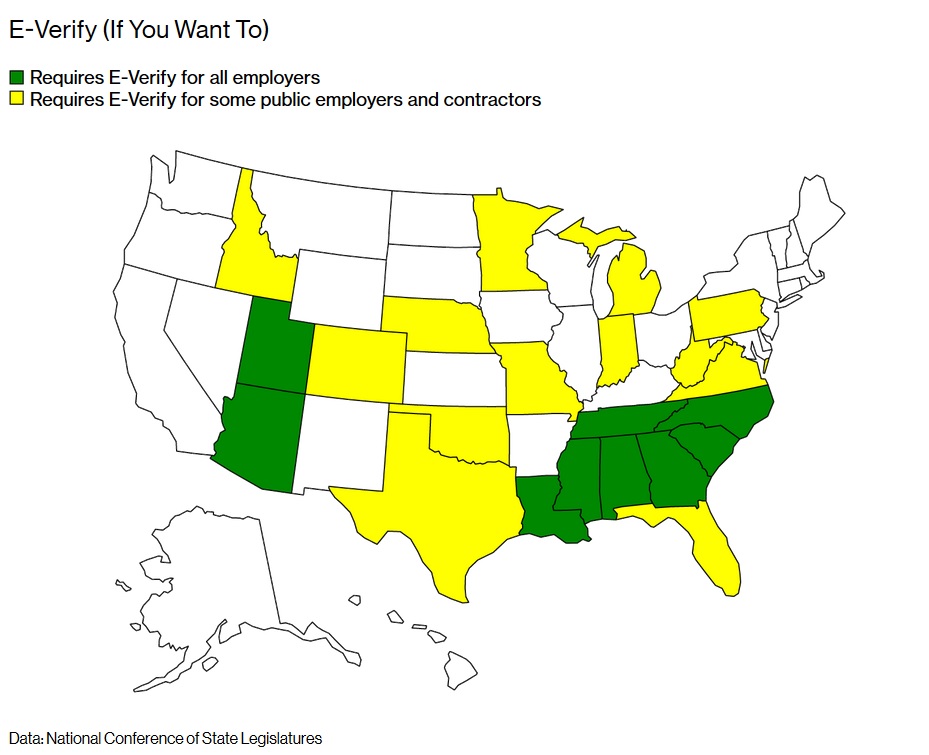

In 2011 states across the Southeast passed laws that threatenedprivate employers with dire consequences—including losing theirlicense to do business—if they didn't enroll with a federal dataservice called E-Verify to check the legal status of new hires. Modeled after 2008measures in Arizona and Mississippi and billed as a rebuke to ado-nothing Obama administration, the laws wentfurther than those in the 13 states that required checks for new hires only by stateagencies or their contractors.

|Seven years later, those laws appear to have been more politicalbark than bite. None of the Southern states that extended E-Verifyto the private sector have canceled a single business license, andonly one, Tennessee, has assessed any fines. Most businesses caughtviolating the laws have gotten a pass.

|Related: Caregivers (and patients) on the losing end ofTrump immigration policy

| In Georgia the departmentcharged with auditing compliance with the E-Verify law has neverbeen given money to do so. In Louisiana, where the law againsthiring unverified employees can lead to cancellation of publiccontracts or loss of business licenses, no contract has beencanceled, no licenses have been suspended, and the state reportszero “actionable” complaints since the mandate went into effect in2012. In Mississippi no one seems to know who enforces the E-Verifylaw. The mandate appears to give that job to its Department ofEmployment Security, which knows nothing about it and referredquestions to the attorney general's office, which says it doesn'tknow who's responsible.

In Georgia the departmentcharged with auditing compliance with the E-Verify law has neverbeen given money to do so. In Louisiana, where the law againsthiring unverified employees can lead to cancellation of publiccontracts or loss of business licenses, no contract has beencanceled, no licenses have been suspended, and the state reportszero “actionable” complaints since the mandate went into effect in2012. In Mississippi no one seems to know who enforces the E-Verifylaw. The mandate appears to give that job to its Department ofEmployment Security, which knows nothing about it and referredquestions to the attorney general's office, which says it doesn'tknow who's responsible.

The same is true in Alabama, where the state labor departmentpoints to the Alabama Law Enforcement Agency, which neitherenforces the law nor knows who does. District attorneys, who fieldcomplaints under the mandate, say enforcement falls to the stateattorney general's office, which hadn't heard that. “What is itwe're supposed to be doing?” spokeswoman Joy Patterson asks. “I'mnot aware of anything like that.”

|Scott Beason, a former state senator who championed Alabama'slaw, laments the lack of enforcement. “We seem to have entered anew age in the state of Alabama, where if the executive branchdoesn't want to enforce a law, they all say they don't know who issupposed to do it.” More than that, the failure to enforce E-Verifylaws underscores how complicated the immigration debate is.

|Even in deep-red states enamored of immigration crackdowns,punishing business is bad politics. Lawmakers “got all thepolitical benefits of supporting immigration enforcement but notthe political cost of hurting business,” says Cato Instituteanalyst Alex Nowrasteh. “These are states that very much want toenforce immigration laws, where the electorate is solidly behind itand the politics is behind it, and even there they don't want toenforce it.”

|The Legal Workforce Act, a bill that would institute a nationalE-Verify system, is expected to be debated on the floor of the U.S.House of Representatives in September. Sponsored by VirginiaRepublican Bob Goodlatte, chairman of the House JudiciaryCommittee, some form of the measure has been pushed for a number ofyears by immigration hard-liners. It's failed to get out of theHouse. The Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR) ispreparing a digital ad campaign meant to embarrass businessopponents of the proposed act, especially produce growers in theWest. FAIR President Daniel Stein says that's just one example ofthe fissures between “the group that underwrites the RepublicanParty and the Republican base.”

|Introduced in the 1990s as a voluntary program, E-Verify becamemandatory for federal contractors in 2009. Businesses enroll bysigning a memorandum of understanding with the U.S. Department ofHomeland Security saying they will use the system for new hires.The department doesn't enforce compliance but does collect datathat suggest not all enrollees are using it. Georgia, for instance,has 101,667 enrolled businesses, the most in the country. It alsohas the lowest percentage—23 percent—of enrollees that e-verified ahire in the past year.

|For businesses that do e-verify, the motivation may be fear offederal immigration raids rather than a state crackdown, sinceparticipation helps protect employers from federal prosecution.It's been against federal law since 1986 to knowingly hireundocumented workers. The “knowingly” language spawned a cottageindustry of fake documents, layered hiring—subcontractors who hiresubcontractors who hire subcontractors—and the use of temp agenciesand independent contractors, all shielding employers from knowledgeof a worker's status. Critics say E-Verify encouragesdiscrimination and is filled with loopholes. It failed to flag theillegal status of Cristhian Rivera, who was accused in the recentdeath of Iowa college student Mollie Tibbetts.

|The laws typically require employers to submit affidavitsshowing they've enrolled in E-Verify to get their business licensesrenewed. South Carolina is the only one of the nine privateE-Verify states that conducts audits. A three-person staff at thestate's Department of Labor, Licensing and Regulation sendsmailings to about 2 percent of employers a year asking for lists ofhires and proof of verification. About 17 percent of last year'sauditees were out of compliance. The state cited 1,631 employersfrom 2013 to 2017. None were punished beyond having to submitquarterly reports for a year.

|Many states with E-Verify laws built in loopholes from thestart, including exemptions for seasonal workers (North Carolina)and farmworkers, fishermen, maids, and nannies (South Carolina).Business groups fought hard for those loopholes. “It was us againstthe Georgia Chamber, the [Atlanta] metro Chamber, and Big Ag,” saysD.A. King, president of the Dustin Inman Society, ananti-immigration group named after a teenager killed in a caraccident where the other vehicle was driven by a person in the U.S.illegally. Georgia doesn't enforce the E-Verify mandate for theprivate sector and has a board to hear complaints about the publicsector. Of the 22 complaints it's received in six years, 20 camefrom King.

|Almost as evidence of their own futility, the E-Verify laws wereabsent from Georgia's recent GOP gubernatorial primary. Despitecampaigning on how tough they would be on immigrants, neithercandidate referred to the laws. The winner, Brian Kemp, ran adssaying he'd haul illegals away in his pickup. “They talked aboutsanctuary cities and rounding up criminal aliens in a truck, allthese distractions,” King says. “The root cause of illegalimmigration is illegal employment. And none of our candidates madea peep about that.”

|Copyright 2018 Bloomberg. All rightsreserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten,or redistributed.

Complete your profile to continue reading and get FREE access to BenefitsPRO, part of your ALM digital membership.

Your access to unlimited BenefitsPRO content isn’t changing.

Once you are an ALM digital member, you’ll receive:

- Critical BenefitsPRO information including cutting edge post-reform success strategies, access to educational webcasts and videos, resources from industry leaders, and informative Newsletters.

- Exclusive discounts on ALM, BenefitsPRO magazine and BenefitsPRO.com events

- Access to other award-winning ALM websites including ThinkAdvisor.com and Law.com

Already have an account? Sign In

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.