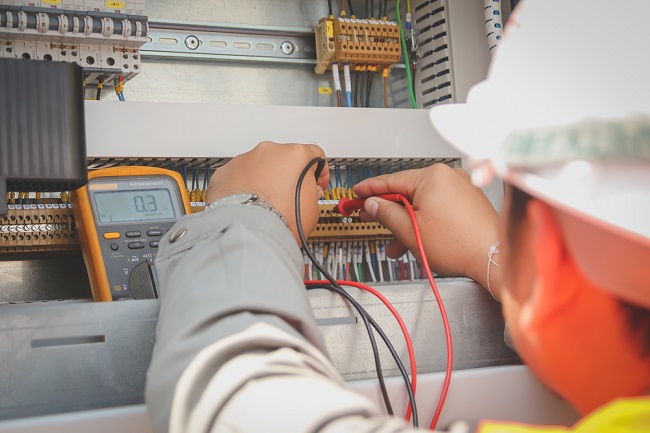

The new blue-collar labor force will need four “distinctively morehuman” core competencies: complex reasoning, social and emotionalintelligence, creativity and certain forms of sensory perception.(Photo: Shutterstock)

The new blue-collar labor force will need four “distinctively morehuman” core competencies: complex reasoning, social and emotionalintelligence, creativity and certain forms of sensory perception.(Photo: Shutterstock)

It's hiring day at Rolls Royce's jet-engine plantnear Petersburg, Virginia. Twelve candidates are divided into threeteams and given the task of assembling a box. Twelve Rolls Royceemployees stand around them, one assigned to each candidate, takingnotes.

|The box is a prop, and the test has nothing to do withprogramming or repairing the robots that make engine parts here.It's about collaborative problem solving.

|“We are looking at what they say, we are looking at what theydo, we are looking at the body language of how they areinteracting,” says Lorin Sodell, the plant manager.

|Related: Prepare for a skills shift: what employers need todo to adapt their workforce

|For all the technical marvels inside this fully automated,eight-year-old facility, Sodell talks a lot about soft skills such as troubleshooting andintuition.

|“There are virtually no manual operations here anymore,” hesays. People “aren't as tied to the equipment as they were in thepast, and they are really freed up to work on more higher-orderactivities.”

|Automation paradox

Call it the automation paradox: The infusion of artificialintelligence, robotics and big data into the workplace is elevatingthe demand for people's ingenuity, to reinvent a process or rapidlysolve problems in an emergency.

|The new blue-collar labor force will need four “distinctivelymore human” core competencies for advanced production: complexreasoning, social and emotional intelligence, creativity andcertain forms of sensory perception, according to Jim Wilson, amanaging director at Accenture Plc.

|“Work in a certain sense, and globally in manufacturing, isbecoming more human and less robotic,” says Wilson, who helped leadan Accenture study on emerging technologies and employment needscovering 14,000 companies in 14 large, industrialized nations.

|Few narratives in economics and social policy are as alarmist asthe penetration of automation and artificial intelligence into theworkplace, especially in manufacturing.

|Hollowing out

Economists talk about the hollowing-out of middle-incomeemployment. American political discourse is full of nostalgia forhigh-paying blue-collar jobs. The Trump Administration is imposingtariffs and rewriting trade agreements to entice companies to keepplants in the U.S. or even bring them back.

|The stark reality is that automation will continue to erode awayrepetitive work no matter where people do it. But there is also amyth in this narrative that suggests America has permanently lostits edge. The vacant mills in the southeast and Midwest, and thestruggling cities around them, are evidence of how technology andlow-cost labor can rapidly kill off less-agile industries. Thisisn't necessarily a prologue to what's next, however.

|Cutting-edge manufacturing not only involves the extremeprecision of a Rolls Royce turbo-fan disc. It's also moving towardmass customization and what Erica Fuchs calls “parts consolidation”— making more-complex blocks of components so a car, for example,has far fewer parts. This new frontier often involvesexperimentation, with engineers learning through frequent contactwith production staff, requiring workers to make new kinds ofcontributions.

|U.S. can lead

“This is a chance for the U.S. to lead. We have the knowledgeand skills,” says Fuchs, an engineering and public-policy professorat Carnegie Mellon University. “When you move manufacturingoverseas, it can become unprofitable to produce with the mostadvanced technologies.”

|The new alliance between labor and smart machines is apparent onRolls Royce's shop floor. The 33 machinists aren't repeating onesingle operation but are responsible for the flow of fan-disc andturbine-blade production. They are in charge of their day,monitoring operations, consulting with engineers and maintainingequipment.

|This demonstrates what automation really does: It changes theway people use their time. A visit to the plant also reveals whyfactory workers in automated operations need more than someknowledge of machine-tool maintenance and programming: They arepart of a process run by a team.

|Industrial jewelry

Sodell opens what looks like a giant suitcase. Inside is atitanium disc about the size of a truck tire. Unfinished, it costs$35,000, and it's worth more than twice that much once it'smachined as closely as possible to the engineers' perfectmathematical description of the part. The end product is so finelycut and grooved it resembles a piece of industrial jewelry.

|“I am not at all bothered by the fact that there isn't a personhere looking after this,” he says, standing next to a cuttingstation about half the size of a subway car. Inside, a robot arm ismeasuring by itself, picking out its own tools and recording dataalong the way.

|Variations in the material, temperatures and vibration can causethe robot to deviate from the engineers' model. So human instinctand know-how are required to devise new techniques that reduce thevariance. Just by looking at the way titanium is flecking off adisc in the cutting cell, for example, a machinist can tellsomething is off, Sodell says. With expensive raw materials, suchtechnical acumen is crucial.

|Perfect model

It's also important because current artificial-intelligencesystems don't have full comprehension of non-standard events, theway a GPS in a car can't comprehend a sudden detour. And they don'talways have the ability to come up with innovations that improvethe process.

|Sodell says workers are constantly looking for ways to refineautomation and tells the story of a new hire who figured out a wayto get one of the machines to clean itself. He developed a tool andwrote a program that is now part of the production system.

|Technicians start off making $48,000 a year and can earn as muchas $70,000, depending on achievement and skill level. Most need atleast two years of experience or precision-machining certificationfrom a community college. Rolls Royce is collaborating with theseschools and relying on instructors like Tim Robertson, among thefirst 50 people it hired in Virginia. He now teaches advancedmanufacturing at Danville Community College and says it's hard toexplain what work is like at an automated facility. Jobs require alot more mental engagement, he explains, because machinists arelooking at data as much as materials and equipment.

|The Danville program includes a class on talking throughconflict, along with live production where students are required tomeet a schedule for different components in a simulated plant. Thegroup stops twice a day and discusses how to optimize workflow.

|“You can ship a machine tool to any country in the world,”Robertson says. “But the key is going to be the high-leveltechnician that can interact with the data at high-level activityand be flexible.”

|Read more:

- Automation comes for Amazon's white-collarworkers

- 10 jobs projected to have the strongest increasesby 2023

- Automation is going to take jobs, especially forwomen

Copyright 2018 Bloomberg. All rightsreserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten,or redistributed.

Complete your profile to continue reading and get FREE access to BenefitsPRO, part of your ALM digital membership.

Your access to unlimited BenefitsPRO content isn’t changing.

Once you are an ALM digital member, you’ll receive:

- Critical BenefitsPRO information including cutting edge post-reform success strategies, access to educational webcasts and videos, resources from industry leaders, and informative Newsletters.

- Exclusive discounts on ALM, BenefitsPRO magazine and BenefitsPRO.com events

- Access to other award-winning ALM websites including ThinkAdvisor.com and Law.com

Already have an account? Sign In

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.