Employers and insurers say that copay assistanceprograms encourage people to take expensive brand-name drugsinstead of equally effective but cheaper generics. (Photo:Shutterstock)

Employers and insurers say that copay assistanceprograms encourage people to take expensive brand-name drugsinstead of equally effective but cheaper generics. (Photo:Shutterstock)

Without medication to manage her plaque psoriasis, JenniferBrown's face, scalp, trunk and neck periodically become covered inpainful red, flaky patches so dry they crack and bleed.

|She has gotten relief from medications, but they come at a highprice. For a while she was on Humira, made by AbbVie, with anaverage retail price of roughly $8,600 for two monthly injections.When that drug stopped working for her, Brown's doctor switched herto a different drug. Today she is using another injectable,Skyrizi, also by AbbVie, which costs about $36,000 for twoquarterly injections — nearly 40% more annually than Humira.

|Related: Copay accumulator programs: Are the risks worth thesavings?

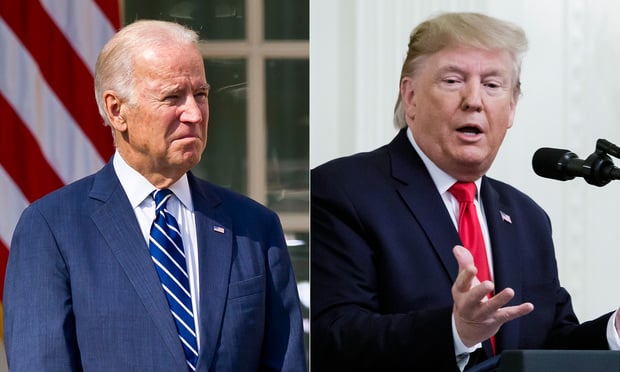

|The pharmaceutical company offers an assistance program to helpconsumers like Brown pay their share of the drug, and that hashelped her cover her copayments. However, she faces the possibilityof higher drug costs under a federal rule finalized this spring by the Trumpadministration.

|The rule, an annual directive that sets health plan standardsfor 2021, permits employers and insurers not to apply drug companycopayment assistance toward enrollees' deductibles andout-of-pocket maximums for any drug. That means only payments madeby the patients themselves would factor into the calculations toreach those spending targets and could make individuals responsiblefor thousands of dollars in drug costs.

|Advocates for consumers with chronic conditions say the rulewill make it harder for patients with conditions such as cancer andmultiple sclerosis who rely on very expensive drugs to affordthem.

|"I understand that the administration doesn't want to encouragepatients to take higher-priced drugs," said Carl Schmid, executivedirector of the HIV + Hepatitis Policy Institute. "But … these arepeople who have HIV and other chronic conditions who take drugsthat don't have generics."

|Patient advocates had hoped the administration would allowemployers and insurers to apply these restrictions only if apatient was taking a brand-name drug that had an appropriategeneric alternative. In the rule that set standards for 2020, theadministration initially seemed to take that approach. But, faced withcriticism by employers and insurers, it said last summer that itwould reconsider the position.

|Drug company programs that provide copayment assistance toconsumers have long been controversial. Employers and insurers saythey encourage people to take expensive brand-name drugs instead ofequally effective but cheaper generics.

|Consumer advocates counter that many of the drugs consumers takefor chronic conditions have no alternative. Research has shown thatgenerics exist for about half of the drugs that offer copayment assistance.

|Drugs to treat patients with hemophilia cost an average $275,000annually, said Kollet Koulianos, senior director of payer relationsat the National Hemophilia Foundation. There are no genericalternatives.

|"We're not talking about $5 coupons in the Sunday paper,"Koulianos said. "We're talking about high-cost specialty drugs,where they have to take this drug month in and month out for years.[Patients] just can't make the math work" without financialhelp.

|The Business Group on Health, which represents large employers,supported the provisions in the final rule that allow employers toopt not to apply the value of drug company copayments for any drugtoward their employees' out-of-pocket spending limits, said SteveWojcik, vice president of public policy. About a third of largeemployers have such programs in place, according to theorganization's annual survey.

|The final rule gives employers flexibility, Wojcik said.

|"If there's not a generic alternative available, a drug couponmay make sense," Wojcik said. "But it also begs the question: Whydoesn't the manufacturer just lower the price at the beginningrather than issue a coupon?"

|The final rule allows state laws regarding "copay accumulators,"as these health plan programs are often called, to supersede thefederal rule. Four states — Arizona, Illinois, Virginia and WestVirginia — have passed laws that limit or prohibit their use,according to Ben Chandhok, senior director of state legislativeaffairs at the Arthritis Foundation. Seventeen states haveconsidered similar bills this year, but it's unlikely any will passgiven the pressure states are under because of the coronaviruspandemic, he said.

|When lawmakers next meet, "they will most likely considerbudget-related bills," Chandhok said.

|Brown, 44, who works in auto insurance claims settlements, livesin Roanoke, Virginia. Her state is one of the fewthat require insurers to count payments made by drug companieson consumers' behalf toward their out-of-pocket spending limits.But her company is self-insured, meaning it pays its employees'claims directly instead of buying state-regulated insurance forthat purpose. So the company isn't bound by Virginia's law andinstead follows federal regulation.

|A few years ago, her employer put a copay accumulator feature onher health insurance plan so the copayment assistance she receivedfrom the drug company for Humira no longer counted toward herdeductible and out-of-pocket maximum spending limit for the year.That meant that once AbbVie's assistance maxed out for the year,she would be on the hook for the drug's full cost until she reachedher deductible and then for cost sharing until she reached herplan's annual out-of-pocket limit.

|The insurance change made her so anxious that she had astress-related flare-up of her psoriasis, and for the first timebroke out on her legs.

|"I can't even describe to you how stressful that was," saidBrown.

|Fortunately, her doctor was able to provide Brown with drugsamples, saving her from paying out-of-pocket for Humira.

|There is no generic alternative for Skyrizi, the drug Browntakes now. This year, she aimed to reduce the odds that she'd beresponsible for high drug payments by switching to a plan with a$2,000 deductible and a $3,000 maximum out-of-pocket spendinglimit. It's more expensive than her previous plan, but it reduceshow much she may owe in drug copayments.

|The AbbVie program will cover up to $16,000 annually in copayassistance for Skyrizi before Brown has to start payingout-of-pocket. She doesn't expect to exceed that level, so shehopes she's off the hook for this year.

|But Brown acknowledges this problem isn't going away, and it's aconstant source of worry.

|"If I don't have the drug, my quality of life would just not beworth living," she said. "So I'll just keep accumulating debt if itcomes down to that."

|KHN (Kaiser HealthNews) is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is aneditorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation),which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

|Read more:

- Federal rule would put consumers on the hook forgreater share of drug copays

- Copay accumulator programs leave consumers on thehook for high drug costs

- Pharmacy benefit managers crack down on copayassistance programs

Complete your profile to continue reading and get FREE access to BenefitsPRO, part of your ALM digital membership.

Your access to unlimited BenefitsPRO content isn’t changing.

Once you are an ALM digital member, you’ll receive:

- Critical BenefitsPRO information including cutting edge post-reform success strategies, access to educational webcasts and videos, resources from industry leaders, and informative Newsletters.

- Exclusive discounts on ALM, BenefitsPRO magazine and BenefitsPRO.com events

- Access to other award-winning ALM websites including ThinkAdvisor.com and Law.com

Already have an account? Sign In

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.