Black families were overcharged somewhere between $3.2 billion and$4 billion (in 2019 dollars) in Chicago alone, researchers havefound. (Photo: Bloomberg)

Black families were overcharged somewhere between $3.2 billion and$4 billion (in 2019 dollars) in Chicago alone, researchers havefound. (Photo: Bloomberg)

(Bloomberg Opinion) –One question is — or should be — central toany assessment of the state of America: Why, more than a centuryand a half after slavery ended, does the typical black family remain so much poorer than the typical whitefamily?

|A new study on housing in Chicago illustratesa big part of the answer: Generation after generation, the U.S.system of real-estate finance has enriched whites at the expense ofblacks.

|Housing has long played a crucial role inAmerican wealth accumulation: People buy homes with federallysubsidized mortgages, build up equity and pass the assetson to their children. But as recently as the 1960s,government policy excluded blacks. In a practiceknown as redlining, the Federal Housing Administration designatedpredominantly black neighborhoods as no-go zones forgovernment-insured mortgage loans. The FHA also wouldn't guaranteeloans for new mixed-race developments: The presence of even asingle black family was enough to warrant rejection.

|Hence, blacks had to find other ways to obtain shelter. One was“contract for deed,” an arrangement usually offered by speculatorswho bought properties expressly for the purpose. Itrequired a down payment and regular monthly installmentsfrom the occupant, but that's where the similarities to amortgage ended. The sale price and effective interest rate tendedto be wildly inflated. The “buyer” assumed all the responsibilitiesof a homeowner, including repairs and taxes, while the “seller”retained title, along with the power to evict for missing even asingle payment. As a result, families who bought “on contract”didn't accumulate equity, and faced a long and precarious path toownership.

|Chicago became a hotbed of contract-for-deedtransactions in the mid-20th century, as large numbers ofblacks — still brutally persecuted in the South — moved to northernindustrial cities in the Great Migration. The city also saw one ofthe country's largest organized rebellions against the practice:The Contract Buyers League, which filed two federal lawsuitsseeking relief from the contracts' onerous provisions. The lawsuitsfailed, but for historians their long lists of homes and tenants(cited as evidence) provide a rare and valuable window into whatwas otherwise a largely undocumented and unregulatedphenomenon.

|Now, researchers — including Jack Macnamara, who as a youngJesuit seminarian helped organize the League –- have tapped thoselawsuits, along with municipal records andthe work of other scholars, to come up with anestimate of how much this one predatory practice, in one city, setback black families. Using data on sales and mortgagerates, they calculated how much each family's payments exceededwhat they would have been if the property had been purchased at theprevailing market price with a conventional mortgage loan. Theythen added it up for all the contract properties they couldidentify from the years 1950 to 1970.

|The outcome: Black families were overcharged somewhere between$3.2 billion and $4 billion (in 2019 dollars). The real estateagents and investors who profited were almost exclusivelywhite, so this represents a direct transfer of wealth from one raceto another. Worse, the contracts' exorbitant terms, along with thelack of equity to borrow against, left black families without themeans to invest in their properties, contributing to the physicaldecline of their neighborhoods.

|The predation didn't end in the 1960s. It evolved. There was theFHA scandal of the 1970s, in which indiscriminatefederal lending and outrightcorruption enabled speculators to sell inner-cityhomes to blacks at inflatedprices, resulting inwidespread foreclosures. There was the subprime boom ofthe 2000s, in which blacks were steered into inappropriatelyexpensive loans that enriched a whole ecosystem ofmortgage-industry professionals, but often left borrowers withnothing but an eviction notice and a bad credit history. In thewake of the subprime bust, investors including private-equity firmshave again targeted the same neighborhoods, buying up houses on thecheap and renting them back to black and other minoritytenants – sometimes under contracts verysimilar to those of the 1960s.

|The investors involved don't necessarily act with racist intent.They exploit blacks because that's where the opportunity is.

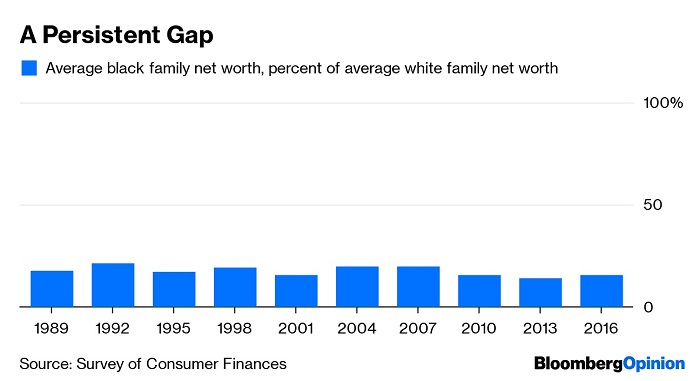

| Black versus white net worth. (Chart:Bloomberg)

Black versus white net worth. (Chart:Bloomberg)

But the effect is the same: Black Americans experience acompletely different kind of finance, one that turns the dream ofhomeownership into a poverty trap. This helps explainwhy, despite narrowing racial disparities inareas such as education and employment, the gap in net worthremains just as large as it was almost three decades ago.

|READ MORE:

|Race, ethnicity play huge role in retirementpreparedness

|The African-American retirement crisis: howauto-portability can help

|Black women's Equal Pay Day highlights massivepay gap

|Copyright 2019 Bloomberg. All rightsreserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten,or redistributed.

Complete your profile to continue reading and get FREE access to BenefitsPRO, part of your ALM digital membership.

Your access to unlimited BenefitsPRO content isn’t changing.

Once you are an ALM digital member, you’ll receive:

- Critical BenefitsPRO information including cutting edge post-reform success strategies, access to educational webcasts and videos, resources from industry leaders, and informative Newsletters.

- Exclusive discounts on ALM, BenefitsPRO magazine and BenefitsPRO.com events

- Access to other award-winning ALM websites including ThinkAdvisor.com and Law.com

Already have an account? Sign In

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.