The U.S.'s great social divide —non-college people in small towns and educated people in cities —has its root in deep economic forces. (Photo:Shutterstock)

The U.S.'s great social divide —non-college people in small towns and educated people in cities —has its root in deep economic forces. (Photo:Shutterstock)

David Autor, a labor economist at the Massachusetts Institute ofTechnology, has a record of attacking the biggest and mostimportant issues. He has raised alarms about disappearing middle-skilled jobs, pointed to the downsidesof trade with China, warned about increasing industrialconcentration and attacked the question of whether automation will kill jobs.

|In a recent lecture at the American Economic Association meetingin Atlanta, Autor attempted to weave many of those threads togetherinto a single story. Paraphrasing heavily, that story goessomething like this: Forty years ago, Americans who didn't go tocollege could move to cities and get good jobs in manufacturing or office work. But starting inabout 1980, these jobs began to disappear, thanks in part tooffshoring and automation. By 2000, manufacturing was in steadyretreat:

| Workers without a collegeeducation were increasingly shunted into low-skilled service jobs —cleaning, security, retail, food service and manual labor.Fortunately, more Americans went to college than before, but theones who didn't were increasingly marginalized.

Workers without a collegeeducation were increasingly shunted into low-skilled service jobs —cleaning, security, retail, food service and manual labor.Fortunately, more Americans went to college than before, but theones who didn't were increasingly marginalized.

Related: Where does a college degree have the biggest impacton income?

|Even as educational inequality was growing, geographicinequality was growing as well. High-skilled occupationsincreasingly clustered in cities, while low-skilled service jobshave become more plentiful outside of urban centers. At the sametime, wages for mid-skilled jobs like manufacturing and office workequalized between cities and rural areas — workers in these jobscan no longer get much of a pay bump by moving into town.

|Thus, a major route to middle-class prosperity has been closedoff. In the old days, even people without a college education couldmove into the big city and work in a factory or office for a goodsalary — now, they might as well stay in their hometowns. As aresult, Autor shows, the urban-rural education gap has widened — in1970, an American in a rural area was only 5 percent less likely tohave a college degree as someone in an urban area, but by 2015 thatgap had grown to 20 points. In other words, the U.S.'s great socialdivide — non-college people in small towns and educated people incities — has its root in deep economic forces.

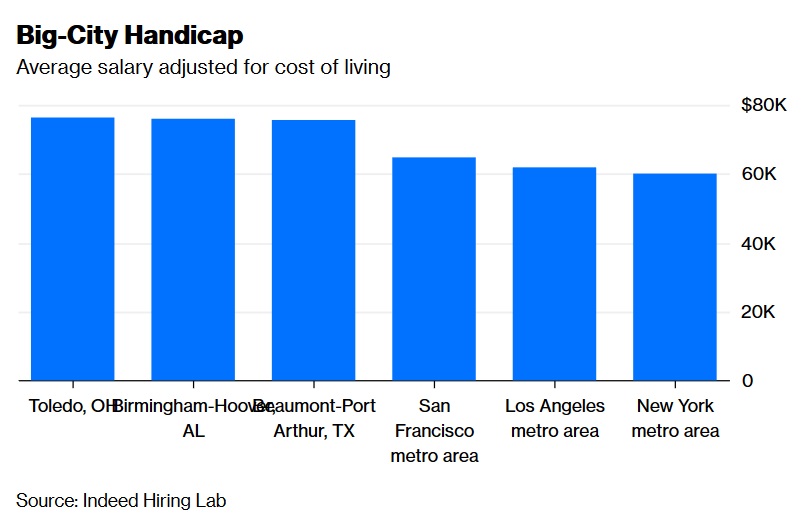

|Actually, Autor's wage data probably understate how badprospects are in big cities for people without college degrees.Rent and other costs of living are much higher in urban areas,meaning a paycheck doesn't go nearly as far there. Jed Kolko, aneconomist at the job-search company Indeed, finds that whensalaries are adjusted for local costs of living, the average workeractually makes less in New York City or Los Angeles than in Toledo,Ohio or Birmingham, Alabama:  Meanwhile, a map by the HamiltonProject at the Brookings Institution, a think tank, shows littlevariation in cost-of-living-adjusted wages across the U.S.

Meanwhile, a map by the HamiltonProject at the Brookings Institution, a think tank, shows littlevariation in cost-of-living-adjusted wages across the U.S.

For college-educated workers, the picture is probably muchdifferent. Autor shows that these workers still get a huge payraise by moving to dense areas — probably more than enough toovercome the increased cost of living.

|Why are cities no longer lands of opportunity for middle-skilledworkers and those without college degrees? The economic forcesdriving urbanization are changing, as the U.S. economy shifts frommanufacturing to knowledge industries like software andfinance.

|Some of this can be explained by virtue of the two basiceconomic reasons for cities to exist in a modern economy —agglomeration, and clustering. Agglomeration refers to the tendencyof businesses of all types, but especially manufacturers, to locatenear each other. This happens because employers want to be near toemployees, who want to be near to the businesses they work for andbuy goods from. The result is a city with lots of differentindustries.

|Clustering, on the other hand, refers to the tendency ofcompanies within a single industry, such as technology, to want tobe near each other. Clustering effects are much stronger inknowledge-based industries like tech and finance, because ideas aretheir lifeblood, and workers who live near each other tend to shareideas with each other (and with various different employers).Clustering also arises because of the need for employers to haveaccess to a deep pool of skilled workers. These are the forces thatpower Silicon Valley and other tech clusters.

|As the U.S. economy has transferred manufacturing overseas orautomated it, and as consumers have moved from buying more physicalgoods to buying more digital goods and services, agglomeration hasbecome less important relative to clustering. The smokestack citiesof the last century have given way to tech hubs and financialcenters. Economist Enrico Moretti has documented this developmentin great detail in his book “The New Geography of Jobs.” This shiftcan probably explain many of the trends Autor observes.

|So what's to be done in order to help mid-skilled andnon-college workers live decent, middle-class lives? And how canthe emerging divide between small towns and big cities be arrestedor mitigated? Moretti's idea, which has been echoed by some urbandevelopment activist groups, is to build lots more housing incities, driving down rents and making cities more livable foreveryone. Another idea is to use research universities torevitalize flagging regions by dispersing knowledge workers toless-populated areas.

|But in the end, the government may simply have to step in andintervene on behalf of the services class. Wage subsidies,government health care, income support, portable pensions,pro-union policies, and various other incentives for higher wagescan be deployed to make today's low-skilled jobs more like the goodoffice and factory jobs of yesteryear. The alternative may be towatch non-college workers and small towns fall further behind.

Read more:

- Millennial education, finances driving plummetingdivorce rate

- Lifestyles, tech, globalization driving specificjob growth

- U.S. income inequality rising most amongAsians

Noah Smith ([email protected]) is aBloomberg Opinion columnist. He was an assistant professor offinance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion. Thiscolumn does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorialboard or Bloomberg LP and its owners. To contact theeditor responsible for this story: James Greiff [email protected]

|Copyright 2019 Bloomberg. All rightsreserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten,or redistributed.

Complete your profile to continue reading and get FREE access to BenefitsPRO, part of your ALM digital membership.

Your access to unlimited BenefitsPRO content isn’t changing.

Once you are an ALM digital member, you’ll receive:

- Critical BenefitsPRO information including cutting edge post-reform success strategies, access to educational webcasts and videos, resources from industry leaders, and informative Newsletters.

- Exclusive discounts on ALM, BenefitsPRO magazine and BenefitsPRO.com events

- Access to other award-winning ALM websites including ThinkAdvisor.com and Law.com

Already have an account? Sign In

© 2024 ALM Global, LLC, All Rights Reserved. Request academic re-use from www.copyright.com. All other uses, submit a request to [email protected]. For more information visit Asset & Logo Licensing.